Stiefel–Whitney class

In mathematics, in particular in algebraic topology and differential geometry, the Stiefel–Whitney class (named for Eduard Stiefel and Hassler Whitney) is an example of a  characteristic class associated to real vector bundles.

characteristic class associated to real vector bundles.

Contents |

Introduction

General presentation

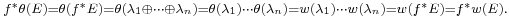

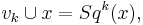

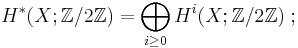

For a real vector bundle E, the Stiefel–Whitney class of E is denoted by w(E). It is an element of the cohomology ring

here X is the base space of the bundle E, and Z/2Z (often alternatively denoted by Z2) is the commutative ring whose only elements are 0 and 1. The component of w(E) in Hi(X; Z/2Z) is denoted by wi(E) and called the i-th Stiefel–Whitney class of E. Thus w(E) = w0(E) + w1(E) + w2(E) + ⋅⋅⋅, where each wi(E) is an element of Hi(X; Z/2Z).

The Stiefel–Whitney class w(E) is an invariant of the real vector bundle E; i.e., when F is another real vector bundle which has the same base space X as E, and if F is isomorphic to E, then the Stiefel–Whitney classes w(E) and w(F) are equal. (Here isomorphic means that there exists a vector bundle isomorphism E → F which covers the identity idX : X → X.) While it is in general difficult to decide whether two real vector bundles E and F are isomorphic, the Stiefel–Whitney classes w(E) and w(F) can often be computed easily. If they are different, one knows that E and F are not isomorphic.

As an example, over the circle S1, there is a line bundle (i.e. a real vector bundle of rank 1) that is not isomorphic to a trivial bundle. This line bundle L is the Möbius strip (which is a fiber bundle whose fibers can be equipped with vector space structures in such a way that it becomes a vector bundle). The cohomology group H1(S1; Z/2Z) has just one element other than 0. This element is the first Stiefel–Whitney class w1(L) of L. Since the trivial line bundle over S1 has first Stiefel–Whitney class 0, it is not isomorphic to L.

However, two real vector bundles E and F which have the same Stiefel–Whitney class are not necessarily isomorphic. This happens for instance when E and F are trivial real vector bundles of different ranks over the same base space X. It can also happen when E and F have the same rank: the tangent bundle of the 2-sphere S2 and the trivial real vector bundle of rank 2 over S2 have the same Stiefel–Whitney class, but they are not isomorphic. However, if two real line bundles over X have the same Stiefel–Whitney class, then they are isomorphic.

The Stiefel–Whitney classes for real vector bundles are analogs of the Chern classes, which are characteristic classes for complex vector bundles.

Origins

The Stiefel–Whitney classes wi(E) get their name because Eduard Stiefel and Hassler Whitney discovered them as mod-2 reductions of the obstruction classes to constructing n − i + 1 everywhere linearly independent sections of the vector bundle E restricted to the i-skeleton of X. Here n denotes the dimension of the fibre of the vector bundle F → E → X.

To be precise, provided X is a CW-complex, Whitney defined classes Wi(E) in the i-th cellular cohomology group of X with twisted coefficients. The coefficient system being the (i − 1)-st homotopy group of the Stiefel manifold of (n − i + 1) linearly independent vectors in the fibres of E. Whitney proved Wi(E) = 0 if and only if E, when restricted to the i-skeleton of X, has (n − i + 1) linearly-independent sections.

Since πi−1Vn−i+1(F) is either infinite-cyclic or isomorphic to Z/2Z, there is a canonical reduction of the Wi(E) classes to classes wi(E) ∈ Hi(X; Z/2Z) which are the Stiefel–Whitney classes. Moreover, whenever πi−1Vn−i+1(F) = Z/2Z, the two classes are identical. Thus, w1(E) = 0 if and only if the bundle E → X is orientable.

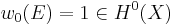

The w0(E) class contains no information, because it is equal to 1 by definition. Its creation by Whitney was an act of creative notation, allowing the Whitney sum Formula w(E1 ⊕ E2) = w(E1)w(E2) to be true. However, for generalizations of manifolds (namely certain homology manifolds), one can have w0(M) ≠ 1: it only needs to equal 1 mod 8.

Definitions

Throughout, Hi(X; G) denotes singular cohomology of a space X with coefficients in the group G. The word map means always a continuous function between topological spaces.

Axiomatic definition

The following set of axioms provides a unique way (the Stiefel-Whitney characteristic class) w of associating to finite rank real vector bundles with paracompact base a class of the mod-2 cohomology of the base: (here  denotes the ring of mod-2 integers.)

denotes the ring of mod-2 integers.)

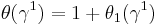

- Normalization: The Whitney class of the tautological line bundle over the real projective space

is non trivial, ie

is non trivial, ie ![w(\gamma^1_1)= 1 %2B a \in H^*(\mathbb RP^1;\mathbb Z_2)= \mathbb Z_2[a]/(a^2)](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/e417afdf56ac403037a7d1572561ef3f.png) .

. - Rank:

, and for i above the rank of E,

, and for i above the rank of E,  , that is,

, that is,  .

. - Whitney product formula:

, that is, the Whitney class of a direct sum is the cup product of the summands' classes.

, that is, the Whitney class of a direct sum is the cup product of the summands' classes. - Naturality:

for any real vector bundle

for any real vector bundle  and map

and map  , where

, where  denotes the pullback vector bundle.

denotes the pullback vector bundle.

The uniqueness of these classes is proved for example, in section 17.2 – 17.6 in Husemoller or section 8 in Milnor and Stasheff. There are several proofs of the existence, coming from various constructions, with several different flavours, their coherence is ensured by the unicity statement.

Definition via infinite Grassmanians

The infinite Grassmannians and vector bundles

This section describes a construction using the notion of classifying space.

For any vector space V, let  denote the Grassmannian, the space of n-dimensional linear subspaces of V, and denote the infinite Grassmannian

denote the Grassmannian, the space of n-dimensional linear subspaces of V, and denote the infinite Grassmannian

.

.

Recall that it is equipped with the tautological bundle  , a rank n vector bundle that can be defined as the subbundle of the trivial bundle of fiber V whose fiber at a point

, a rank n vector bundle that can be defined as the subbundle of the trivial bundle of fiber V whose fiber at a point  is the subspace represented by Ẃ.

is the subspace represented by Ẃ.

Let  , be a continuous map to the infinite Grassmannian. Then, up to isomorphism, the bundle induced by the map f on X

, be a continuous map to the infinite Grassmannian. Then, up to isomorphism, the bundle induced by the map f on X

depends only on the homotopy class of the map ![[f]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/7b93cec8a8b3e110392556212941efcd.png) . The pullback operation thus gives a morphism from the set

. The pullback operation thus gives a morphism from the set

of maps  modulo homotopy equivalence, to the set

modulo homotopy equivalence, to the set

of isomorphism classes of vector bundles of rank n over X.

The important fact in this construction is that if X is a paracompact space, this map is a bijection. This is the reason why we call infinite Grassmannians the classifying spaces of vector bundles.

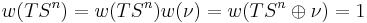

The case of line bundles

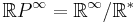

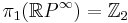

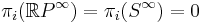

We now restrict the above construction to line bundles, ie we consider the space

of line bundles over X. The Grassmannian of lines  is just the infinite projective space

is just the infinite projective space

,

,

which is doubly covered by the infinite sphere  by antipody. This sphere

by antipody. This sphere  is contractible, so we have

is contractible, so we have

and

and  for all

for all  .

.

Hence  is the Eilenberg-Maclane space

is the Eilenberg-Maclane space  .

.

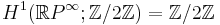

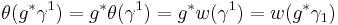

It is a property of Eilenberg-Maclane spaces, that

for any X, with the isomorphism given by  , where

, where  is the generator

is the generator

.

.

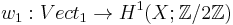

Applying the former remark that ![\alpha:[X, Gr_1] \to Vect_1(X)](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/84e8554d3a19e2b48e8f07857c82ad52.png) is also a bijection, we obtain a bijection

is also a bijection, we obtain a bijection

;

;

this defines the Stiefel–Whitney class  for line bundles.

for line bundles.

The group of line bundles

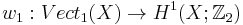

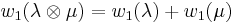

If  is considered as a group under the operation of tensor product, then the Stiefel-Whitney class is an isomorphism:

is considered as a group under the operation of tensor product, then the Stiefel-Whitney class is an isomorphism:  is an isomorphism, that is

is an isomorphism, that is  for all line bundles

for all line bundles  .

.

For example, since  , there are only two line bundles over the circle up to bundle isomorphism: the trivial one, and the open Möbius strip (i.e., the Möbius strip with its boundary deleted).

, there are only two line bundles over the circle up to bundle isomorphism: the trivial one, and the open Möbius strip (i.e., the Möbius strip with its boundary deleted).

The same construction for complex vector bundles shows that the Chern class defines a bijection between complex line bundles over X and  , because the corresponding classifying space is

, because the corresponding classifying space is  , a

, a  . This isomorphism is true for topological line bundles, the obstruction to injectivity of the Chern class for algebraic vector bundles is the Jacobian variety.

. This isomorphism is true for topological line bundles, the obstruction to injectivity of the Chern class for algebraic vector bundles is the Jacobian variety.

Properties

Topological interpretation of vanishing

whenever

whenever  .

.- If

has

has  sections which are everywhere linearly independent then the l top degree Whitney classes vanish:

sections which are everywhere linearly independent then the l top degree Whitney classes vanish:  .

. - The first Stiefel–Whitney class is zero if and only if the bundle is orientable. In particular, a manifold M is orientable if and only if

.

. - The bundle admits a spin structure if and only if both the first and second Stiefel–Whitney classes are zero.

- For an orientable bundle, the second Stiefel–Whitney class is in the image of the natural map

(equivalently, the so-called third integral Stiefel–Whitney class is zero) if and only if the bundle admits a spinc structure.

(equivalently, the so-called third integral Stiefel–Whitney class is zero) if and only if the bundle admits a spinc structure. - All the Stiefel–Whitney numbers of a smooth compact manifold X vanish if the manifold is a boundary (unoriented) of a smooth compact manifold. This condition is in fact also sufficient.

Uniqueness of the Stiefel–Whitney classes

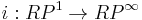

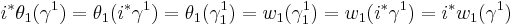

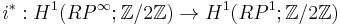

The bijection above for line bundles implies that any functor  satisfying the four axioms above is equal to w, by the following argument. The second axiom yields

satisfying the four axioms above is equal to w, by the following argument. The second axiom yields  . For the inclusion map

. For the inclusion map  , the pullback bundle

, the pullback bundle  is equal to

is equal to  . Thus the first and third axiom imply

. Thus the first and third axiom imply  . Since the map

. Since the map  is an isomorphism,

is an isomorphism,  and

and  follow. Let

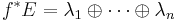

follow. Let  be a real vector bundle of rank

be a real vector bundle of rank  over a space

over a space  . Then

. Then  admits a splitting map, i.e. a map

admits a splitting map, i.e. a map  for some space

for some space  such that

such that  is injective and

is injective and  for some line bundles

for some line bundles  . Any line bundle over

. Any line bundle over  is of the form

is of the form  for some map

for some map  , and

, and  by naturality. Thus

by naturality. Thus  on

on  . It follows from the fourth axiom above that

. It follows from the fourth axiom above that

Since  is injective,

is injective,  . Thus the Stiefel–Whitney class is the unique functor satisfying the four axioms above.

. Thus the Stiefel–Whitney class is the unique functor satisfying the four axioms above.

Non-isomorphic bundles with the same Stiefel–Whitney classes

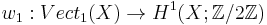

Although the map  is a bijection, the corresponding map is not necessarily injective in higher dimensions. For example, consider the tangent bundle

is a bijection, the corresponding map is not necessarily injective in higher dimensions. For example, consider the tangent bundle  for n even. With the canonical embedding of

for n even. With the canonical embedding of  in

in  , the normal bundle

, the normal bundle  to

to  is a line bundle. Since

is a line bundle. Since  is orientable,

is orientable,  is trivial. The sum

is trivial. The sum  is just the restriction of

is just the restriction of  to

to  , which is trivial since

, which is trivial since  is contractible. Hence

is contractible. Hence  . But

. But  is not trivial; its Euler class

is not trivial; its Euler class ![e(TS^n) = \chi(TS^n)[S^n] = 2[S^n] \not =0](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/54d0a071b36f0eb1580e5f05131196c0.png) , where

, where ![[S^n]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/0a002f8806ecf43aaffe03d674645492.png) denotes a fundamental class of

denotes a fundamental class of  and

and  the Euler characteristic.

the Euler characteristic.

Related invariants

Stiefel–Whitney numbers

If we work on a manifold of dimension n, then any product of Stiefel–Whitney classes of total degree n can be paired with the  -fundamental class of the manifold to give an element of

-fundamental class of the manifold to give an element of  , a Stiefel–Whitney number of the vector bundle. For example, if the manifold has dimension 3, there are three linearly independent Stiefel–Whitney numbers, given by

, a Stiefel–Whitney number of the vector bundle. For example, if the manifold has dimension 3, there are three linearly independent Stiefel–Whitney numbers, given by  . In general, if the manifold has dimension n, the number of possible independent Stiefel–Whitney numbers is the number of partitions of n.

. In general, if the manifold has dimension n, the number of possible independent Stiefel–Whitney numbers is the number of partitions of n.

The Stiefel–Whitney numbers of the tangent bundle of a smooth manifold are called the Stiefel–Whitney numbers of the manifold. They are known to be cobordism invariants. It was proven by Lev Pontrjagin that if B is a smooth compact (n+1)–dimensional manifold with boundary equal to M, then the Stiefel-Whitney numbers of M are all zero.[1] Moreover, it was proved by René Thom that if all the Stiefel-Whitney numbers of M are zero then M can be realised as the boundary of some smooth compact manifold.[2]

One Stiefel–Whitney number of importance in surgery theory is the de Rham invariant of a (4k+1)-dimensional manifold,

Wu classes

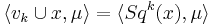

The Stiefel–Whitney classes  are the Steenrod squares of the Wu classes

are the Steenrod squares of the Wu classes  defined by Wu Wenjun in (Wu 1955). Most simply, the total Stiefel–Whitney class is the total Steenrod square of the total Wu class:

defined by Wu Wenjun in (Wu 1955). Most simply, the total Stiefel–Whitney class is the total Steenrod square of the total Wu class:  Wu classes are most often defined implicitly in terms of Steenrod squares, as the cohomology class representing the Steenrod squares:

Wu classes are most often defined implicitly in terms of Steenrod squares, as the cohomology class representing the Steenrod squares:  or more narrowly

or more narrowly  .[3]

.[3]

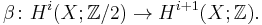

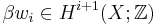

Integral Stiefel–Whitney classes

The element  is called the

is called the  integral Stiefel–Whitney class, where β is the Bockstein homomorphism, corresponding to reduction modulo 2,

integral Stiefel–Whitney class, where β is the Bockstein homomorphism, corresponding to reduction modulo 2,  :

:

For instance, the third integral Stiefel–Whitney class is the obstruction to a Spinc structure.

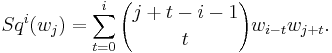

Relations over the Steenrod algebra

Over the Steenrod algebra, the Stiefel–Whitney classes of a smooth manifold (defined as the Stiefel-Whitney classes of its tangent bundle) are generated by those of the form  . In particular, the Stiefel–Whitney classes satisfy the Wu formula, named for Wu Wenjun:[4]

. In particular, the Stiefel–Whitney classes satisfy the Wu formula, named for Wu Wenjun:[4]

See also

- Characteristic class for a general survey, in particular Chern class, the direct analogue for complex vector bundles

- Real projective space

References

- ^ Pontrjagin, L. S. (1947). "Characteristic cycles on differentiable manifolds" (in Russian). Math. Sbornik N. S. 21 (63): 233–284.

- ^ Milnor, J. W.; Stasheff, J. D. (1974). Characteristic Classes. Princeton University Press. pp. 50–53. ISBN 0691081220.

- ^ Milnor, J. W.; Stasheff, J. D. (1974). Characteristic Classes. Princeton University Press. pp. 131–133. ISBN 0691081220.

- ^ (May 1999, p. 197)

- D. Husemoller, Fibre Bundles, Springer-Verlag, 1994.

- May, J. P. (1999), A Concise Course in Algebraic Topology, U. Chicago Press, Chicago, http://www.math.uchicago.edu/~may/CONCISE/ConciseRevised.pdf, retrieved 2009-08-07

![[X; Gr_n]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/166eccad7a8f7d29082dabe656488f83.png)

![[X; \R P^1] = H^1(X; \Z/2\Z)](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/4228342ceec351f1de26f134c9764066.png)